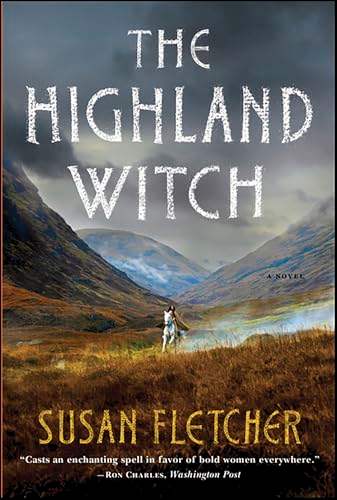

Susan Fletcher won the Whitbread First Novel Award in 2004 for “Eve Green” set in the remote Welsh mountains and shares with “Witch Light” themes of emerging womanhood and the cost of fitting in. Over the previous three hundred years it is estimated that over 100,000 women – mostly knowledgeable, independent, old or outspoken women – stood trial, accused of witchcraft.” The Witchcraft Act of 1735 put an end to the generations of fear and persecution. “The last execution of a so-called witch in Britain was in 1727. Similarly, the voice that Fletcher gives to Corrag, a woman who really lived, still resonates long after finishing the book.Īccording to the “Witch Light” afterword: Hilary Mantel’s imagining of the interior life of Thomas Cromwell is utterly convincing, albeit fictional. There’s a lot to be said for making difficult historical themes accessible through fiction, and it’s often women writers who have the audacity to do it. However, similar charges of anachronism have been levelled at Hilary Mantel’s magnificent “Wolf Hall” and “Bring Up The Bodies”, as well as the historical novels of writers like Philippa Gregory. It crossed my mind that Corrag must surely have had a copy of Elizabeth Gilbert’s “Eat, Pray, Love” knocking around somewhere in her hovel. Yet at odd times the book felt anachronistic, ticking as it does so many modern-day boxes. I loved huge swathes of “Witch Light”, and Corrag’s intimacy with nature is irresistible: she transports tiny snails and moths in her wild and unwashed hair, and communes with stags. I am myself drawn to these themes and to the notion that older women with a close-to-nature inclination and a stubborn streak were most likely to be identified, and even to self-identify, as witches. It combines many current trends: the fictionalisation of real lives and historical events evocation of nature, environment and place foraging, herbal medicine and living off the land. The book plants the Highlands in the reader’s soul and its imagery is unforgettable. Imprisoned and condemned to burn, Corrag tells her life story to Charles Leslie, an undercover Catholic supporter of the Stuart cause.

The story has a dual narrative – it’s told mainly by Corrag, a kind of child-woman falsely tagged as a witch, but guilty of having tipped off the MacDonald clan about their imminent betrayal and slaughter by Protestant forces. “Witch Light” is about early Catholic resistance to William III in the Highlands of Scotland, and the Glencoe Massacre. Susan Fletcher’s novel “Witch Light” is set in 1692, a handful of years after my Huguenot ancestors fled France and landed in England – hopeful of a warm welcome, since the Glorious Revolution of 1688 had ousted James II (a king too prone to Catholicism) and installed Protestant William III on the throne.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)